Drummer Mike Melito admires the relaxed brand of swing and bluesy compositions that typify hard bop, so much so that he believes today’s artists omit a crucial rhythmic element that distinguishes this music, apart from the challenging harmony and technique.

‘The main thing with hard bop that really gets me, and why it’s definitely different today than it was back in the ’50s, is the intensity levels were greater back then,” Melito said. “The rhythm sections weren’t as on top of the beat. Right now, if you go hear most guys, everything sounds _ pushed. Everybody tries to get so much fake forward motion.”

With little fanfare, Melito has carried on hard bop’s behind-the-beat tradition for roughly 25 years. Growing up in Rochester, N.Y., he learned many of his lessons

onstage. He backed the late Joe Romano, a saxophonist with Buddy Rich and the Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Orchestra, before performing throughout upstate New York with artists such as tenor saxophonist J.R.Monterose.

Melito’s education culminated with a careful study of hard bop recordings, especially the classic albums Blue Note released in the mid-1950s and early 1960s. While drummers like Philly Joe Jones, Art Taylor, Jimmy Cobb, and Art Blakey played forcefully, Melito said they also had a knack for restraint—for playing “under” soloists rather than overwhelming them.

In addition, drummers of this era mastered the art of “tippin’.” That is while accompanying a soloist, they would emphasize the ride cymbal more than the snare and bass drums. “The ride cymbal was very relaxed, and the pattern of the ride cymbal stayed straight. It didn’t get nutty,” Melito said. “That fascinated me because it never sounded boring.”’

Melito spotlights this style on his fourth self-released album, In The Tradition. The session pairs the drummer’s homegrown rhythm section with out-of-towners such as tenor saxophonist Grant Stewart, bass player Neal

Miner and trumpeter John Swana. By including bop tunes like Sonny Clark’s “Junka,’”’ Hank Mobley’s ‘“Hankerin’” and Tadd Dameron’s“Good Bait,” Melito not only preserves a rhythmic approach but also a repertoire.

“The melodies were very lyrical, and they were a little more accessible in some ways,” he said. “The bebop melodies were a little bit faster. Hard Bop had more blues influence. There weren’t as many notes in the heads. Every note in hard bop during the ’50s meant something.”

Stewart, a frequent collaborator, said Melito plays an unsung role in the jazz world.

‘‘He’s a great drummer, but he also has a strong concept musically, which is very important,” Stewart said. “He’s important for the music in general because outside of New York City you don’t hear a lot of guys playing like that. I don’t feel like he’s trying to recreate the music. It’s very much a living thing when I play with him.”

Melito anchors the house band at Rochester’s Strathallan Hotel, a venue that books musicians such as guitarist Peter Bernstein and saxophonists Eric Alexander, Vincent Herring, and Stewart. Not surprisingly, the drummer expresses concern about the legacy of hard bop, especially when he observes the scene in the big city downstate.

“T see the music in New York City has changed a lot,” Melito said. “Every time I come down it’s a little more out, and drummers are bashing more. I only see about 15 or 20 guys that play hard bop authentically. I think the reason why is because it’s not really being taught in schools, it’s not really being mentioned in colleges. Heck, I’ve run into people that teach jazz history who don’t even know who Sonny Clark 1s.”

Eric Fine

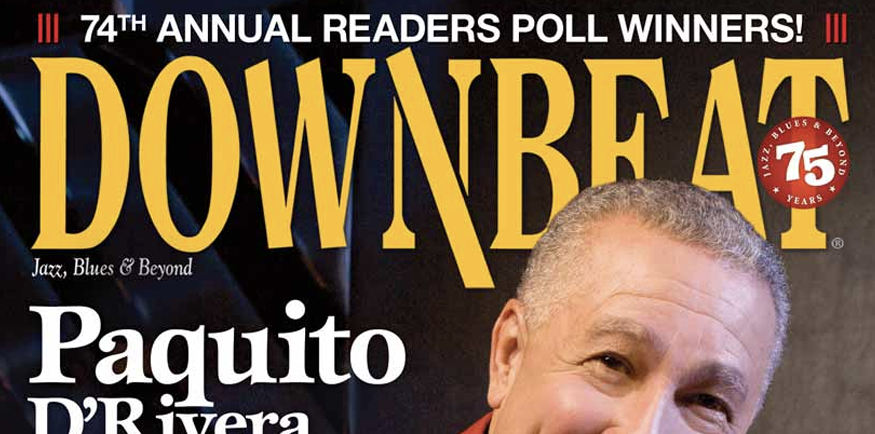

Downbeat Magazine

DOWNLOAD